Posts Tagged ‘policies and procedures’

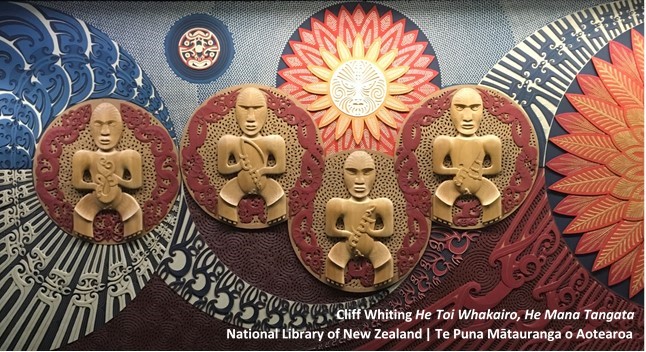

Policy and Procedure Templates – generic & customised

Policy and procedure templates can take you from the bottom of the hill straight to the top.

Most organisations need policies and procedures. But getting your policies sorted can feel like an uphill battle that doesn’t ever end. Templates though can, depending on the type you choose, give you the basic structure to get you started through to all the policy content you need.

To help you make the best choice, we’re reviewing a range of different template options – considering their pros and cons. The good news for social, health, education and housing agencies is that you can access all options through The Policy Place.

Starter Policy and Procedure Templates

If you’re wanting a policy template that gives you a structure to start with, there are a few options around that basically offer advice about policy writing. They typically give you a policy structure along the lines of headings like Purpose; Policy; Procedures; Responsibilities; Related Documents and Policies.

The Workplace Policy Builder is a good example.

Having a structure can help get you started and is a good option if you’re into the DIY and freebies. However, you’ve still got all the hard work of policy creation to do.🤔 Not only that. You also have to keep the content reviewed and updated for currency with law, regulations, and other requirements.

Area-specific Policies

There are lots of policy templates on the market aimed at particular areas like Human Resources and Health and Safety. Sometimes the products come with additional advisory services like HR advice and support. They are a good option if you want access to particular knowledge and expertise.

BUT…

These products can be expensive.

AND…

They can be challenging to implement because they are not typically focused on your particular organisational context. Although they may incorporate some branding and sometimes, an introduction from the CE, they usually apply generally, which comes through in the content.

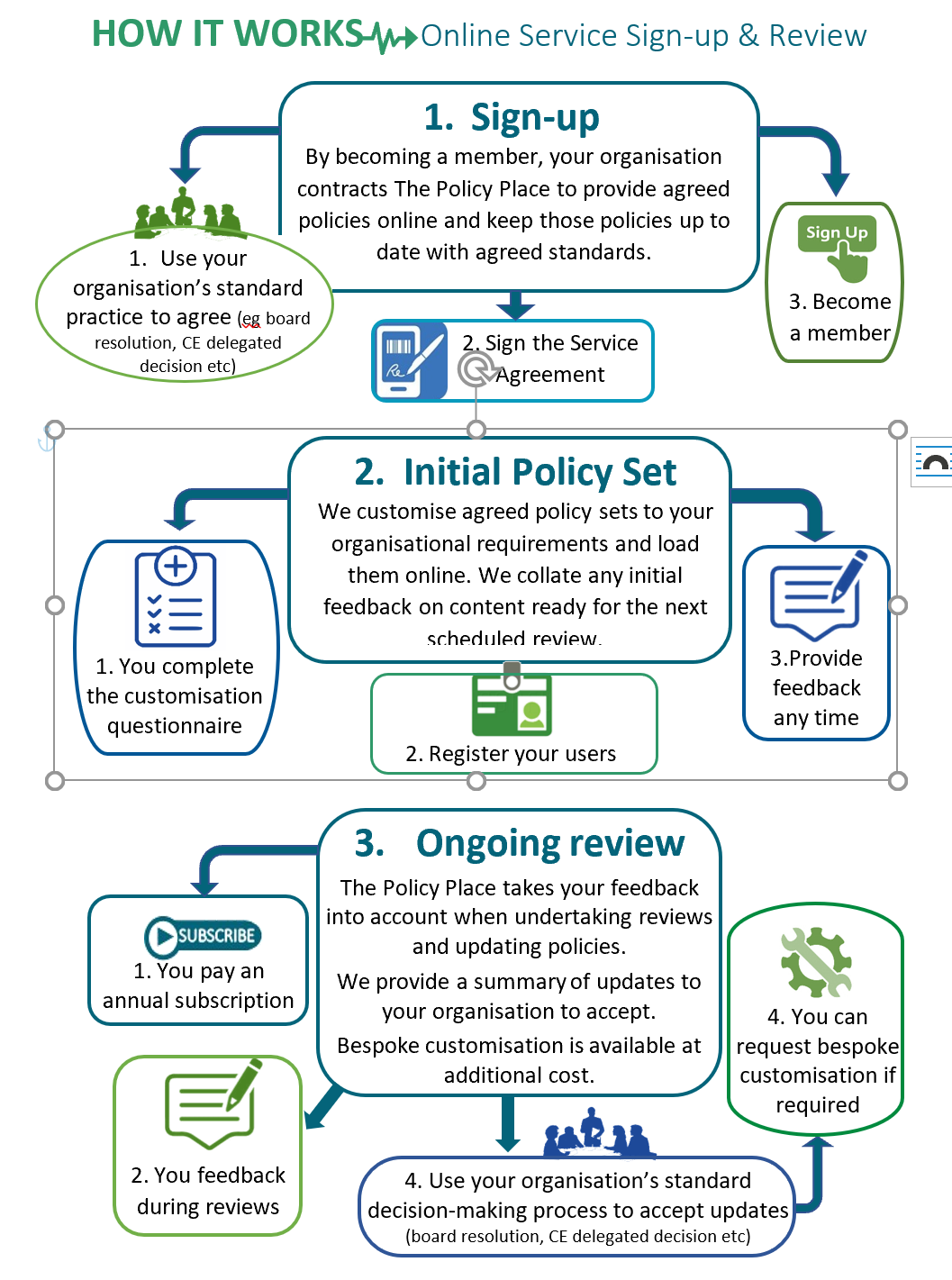

The Policy Place online policy service overcomes these problems:

![]()

- We are not wholly generic. We provide core policy content but specifically for different contexts of social services, health, disability, housing and education and to a limited extent for an organisation itself.

- We are cost-effective because we address common policy needs of organisations associated with law, regulations and compliance standards and want to be accessible to cash-strapped non-profits and start-ups.

- We keep core policy content reviewed and updated for members.

Customised Policy and Procedure Templates

Customised policy products are harder to come by. That’s because they’re usually done by consultants. They can be great because they are built around the organisation’s particular needs and incorporate a lot of operational detail.

BUT…..

Customised policies are usually very expensive. This reflects a heavy investment of time by consultants with specialist knowledge.

AND

Customised policies are a one-off product. They are not subject to regular review and updating, which is required for compliance with standards that apply in areas like Health and Disability, Social Services, Training and Housing.

You can have it all

The Policy Place offers you the chance to customise your policies while reaping the benefits of regular reviews and updates of core policy content. Customisation is optional and done by you as the client.

- The system works easily:

- You sign up for the Essentials Package, which the Policy Place puts together for you based on the information you provide and your compliance needs.

- You decide on how you might want to customise – add paragraphs or pages, edit core policy text or grab it all.

- You decide who you want to authorise to customise your policies and authorise them on the system.

Any problems? Contact the Policy Place who wll help.

Your workplace vaccination policy and procedure

You might think it’s easy when it comes to requiring staff to get vaccinated. They should be given the choice – jab or job, right?

Wrong. It’s not so simple at all, especially when it comes to vaccinations for existing staff in frontline positions eg health and social service staff.

It’s a balancing act

There’s some important interests like human rights and public health to think about and balance:

- the right to refuse and give informed consent to medical treatment under the NZ Bill of Rights Act 1990 (sections 10&11); Code of Health and Disability Rights (sections 6 & 7)

- an employer’s obligation to take all due care to provide a safe and healthy workplace

- a worker’s obligation to take reasonable care to avoid causing harm to themselves and others

- the duty on an agency to take reasonable care to avoid causing foreseeable harm to clients, consumers etc.

And, amongst this, community levels of COVID-19 are also relevant and must be considered.

A positive work culture

Good faith and relationships in the workplace are also important to consider. Public debate too easily descends into blaming and name-calling.

You want to avoid to the greatest extent possible division and friction in the workplace about vaccination. The world is divided enough and a positive work culture is integral to retaining staff and achieving good results.

What to cover in your vaccination policy and procedure

See here for our Key Tips for your Workplace Vaccination policy and procedure.

Policy Intent

Another key tip is to be upfront with your policy intent. If you want to encourage vaccination state it, state it at the front or start of your policy. For example, that –

” the organisation supports kaimahi/staff to obtain vaccination as an important way to mitigate risks of infection of COVID 19.”

Likewise, if you’re worried about workplace divide and impact on culture, include it in your intent. As we suggested in Key Tips for your Workplace Vaccination policy and procedure, an important way to show good faith is to get staff input to the development and review of the policy and procedure.

Warning

Warning, ensure your policy requirements are consistent with your intent. If you’re only wanting to encourage vaccination, then stick to that. Don’t venture into mandating vaccination.

Any requirement for vaccination must be justifiable given the risks of a job and an assessment that vaccination as opposed to others measures is the best and safest way of managing those risks. You can’t require vaccination as a way of encouraging it.

Risk assessment

In How your policy and procedure can bridge the vaccination divide we gave some ideas to head off division and disharmony in the workplace in relation to vaccination. A key strategy is to be rational about it.

Your policy and procedure should reflect an objective risk assessment of roles in your workforce. This risk assessment will help justify why vaccination is a requirement for some positions. It will also help you identify roles where vaccination may not be necessary.

Information and support

Where reasonably practicable, support staff to get vaccinated eg time off for them and their dependents to get vaccinated and to recover if there are any after-effects; referral to public health information about vaccination.

Be an open book when it comes to information. Make sure staff are informed about all the issues relating to Covid-19, vaccination and how it’s relevant to their work and whānau.

For staff who are seem more hesitant about vaccination, engage with them in good faith and support them to address their concerns and questions. An in-person or at least one-to-one engagement with the kaimahi/staff member (with the option to invite their whānau) is likely to be most effective.

Check out Key Tips for your Workplace Vaccination policy and procedure for some more ideas about how to support vaccination.

Prove it

Don’t forget to require proof of vaccination in your policy and procedure. Testing regimes have shown the danger of relying on self-reports.

Require the evidence to be kept on file. You are likely to need it if vaccinations are going to be required on a regular or annual basis to be effective.

Address the challenge

Your policy should include a process for kaimahi/staff, who are unable to be vaccinated because of a pre-existing health condition, and for those who refuse vaccination.

You don’t want these staff to hide they are not vaccinated and the risks this brings. So outlining the process and addressing fears like dismissal is important.

Incorporating your Good faith in Employment policy and procedure will be important. The process could involve steps like the following:

- assessment and application of other protections to the relevant staff (eg PPE, masks) for the person to continue in their role in light of the assessed risks (above)

- an agreed change of duties or position where there is less risk

- through to resignation and termination (if unable to adequately address safety risks.)

Get ready

Good news – if you’re a member of our online policy and procedure service, we’ve already got you covered.

If you’re not a member, now’s the time to start on your DIY workplace vaccination policy and procedure. Check out our posts on vaccination and DIY policy and procedure for help.

Are you missing out? Is good policy what you need?

Are you missing out on the benefits of having good up-to-date policies and procedures? In this post, we look at the value of good policy and procedures for organisations of all types.

If you want to get more out of your operating expenses and want more time to spend on other things, then read on.

Policies are multi-functional

Organisational policies and procedures are not just about compliance. They are multi-functional:

- They are like a will. They help avoid the chaos and distress of uncertainty about what to do about a situation.

- They double as a how-to guide for staff when faced with new responsibilities, roles and challenges.

- If you’re expanding into new areas or building new collaborations, policies and procedures can be used to reflect agreement on the important stuff like communication, reporting, information-sharing, expenditure and income allocation.

- They help you manage risks, for example of litigation, penalties, health and safety issues and risks to reputation.

Great bang for your buck. Yet, so many organisations and businesses are not reaping these benefits.

Danger

Too often organisations’ policies and procedures sit in old electronic and paper files, pulled out just for audits then put away again.

To state the obvious, this is dangerous! It’s a bit like not maintaining the structure of your house or whare. Eventually, rot can set in and more damage occur.

Unfortunately, we hear of lots of such calamities. Some publicly-aired ones include:

- injuries in childcare centres where there was no policy and procedure to guide action and as a result, errors were made;

- injury to a person being transported by an agency without sufficient safeguards in place;

- abuse perpetrated against children and disabled people in residential settings where processes for reporting concerns were inadequate; and

- a failure to provide adequate medical treatment where there was no policy and procedure on informed consent and client-centred practice.

Time waster

Without good organisational policies, you’re also likely to be wasting a lot of needless time and energy, for example:

- repeatedly telling staff what to do and having them tell you that they don’t know what to do

- dealing with complaints

- solving recurring problems with ad-hoc responses

- doing fix-its on solutions that were made up by staff because they couldn’t access good guidance.

It’s wasted time; time that could be better spent on yourself or whānau or on other organisational priorities.

What’s good organisational policy and procedure?

To help figure out what state your policies and procedures are in, consider the criteria for policies and procedures in the NZS 8134.1: 2008 Health and Disability Services Standards. Standard 2.3 requires policies and procedures to:

- align with current good practice and service delivery

- meet legislative requirements

- be reviewed regularly

- be supported by a document control system to ensure that old versions of policies are not being used.

Guidance for NZS 8134.3.1:2008 recommends additional criteria; that policies and procedures should:

- be written and relevant to the organisation

- be sufficiently flexible to respond to consumer needs

- have a user-friendly format

- contain appropriate technical information

- be accessible to all staff

- be developed and regularly reviewed with relevant service providers

- identify helpful links (ie to other documents)

See here for how the Policy Place online policy and procedure service measures up.

Where to start

The task of reviewing and updating policies and procedures can feel overwhelming. It can be hard to know where to start.

If you’re into the DIY approach, as a first step get updated on legislation changes. Take a look at our post outlining key legislation changes over the last year. At the very least you will need to review and update your policies using the legislation and the standards with which you much comply (ie SASS or HD stds.) Involve staff, research and reflect good practise literature.

Let us handle it

You can let go of the stress and give us the job to do. At the Policy Place we are reviewing and updating organisations’ policies and procedures all the time. You get the benefits of policies and procedures that reflect cross-sector knowledge of good practice and policy and procedure expertise.

We give you policies and procedures fit for the 21st century with our online service. We keep them updated and regularly reviewed so you, your board and staff, have a lot less to worry about and a lot more time and energy for the things you want to do (eg recreation and leisure, other work priorities).

Book your free policy consultation

Email us about your policy and procedure needs.

Online policies and procedures – so easy!

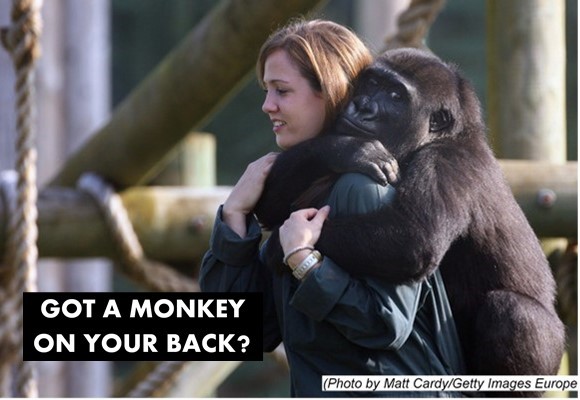

Get that makimaki/monkey off your back

There’s been a lot of change in law, policy and practice recently affecting social, health and disability services. There is likely to be more.

In this post, we overview some key changes to consider when reviewing and updating your organisation’s policies and procedures.

If policy review and updating feels like a makimaki/monkey on your back, contact us now for help. You can schedule a free 30 minute consultation about your needs and your best policy solution. We can take care of the reviews and updating.

If you’re a DIY policy person, tick off these changes as you review your organisation’s policies and procedures.

Legislation changes

Key changes that have commenced this year have been:

- new provision for family violence leave and variation of employment terms for staff affected by family violence

- changes to the law relating to family violence including how and when family violence information can be shared between authorised services and persons

- changes relating to information-sharing for child protection and wellbeing purposes

- extension of Oranga Tamariki legislation (statutory care and youth justice) to under 18 years (was previously up to 17 years)

- more support for young people leaving statutory care or custody up to 25 years

- new principles to guide decisions and interventions under the Oranga Tamariki legislation (eg addressing mana tamaiti, recognition of whakapapa and involvement of those with whanaungatanga responsibilities)

- new requirements on the CE of Oranga Tamariki to enter strategic partnerships with iwi, to give practical effect to Te Tiriti o Waitangi and to report and monitor performance on outcomes for tamariki Māori

- the introduction of new care standards setting minimum requirements for the statutory care of tamariki.

Practice

And don’t forget relevant practice and sector developments that are important enough to incorporate into your policies and procedures, for example:

- stronger recognition across sectors of whānau-centric practice

- more recognition of the need for trauma-informed responses

- move from 3 Ps Treaty framework to article-based framework

- more focus on workplace health and wellbeing

- focus on cultural safety and cultural competency

- mainstreaming – equality and accessibility

- individualised funding.

Quit feeding the makimaki!

Usually, people contact us because they know their policies and procedures are not up to date. They are busy managing services like social housing, family violence intervention, care, mental health, counselling, perpetrator programmes, family support, sexual violence services etc.

They haven’t got the time to keep their organisations’ policies and procedures up-to-date. They no longer want the worry of it.

If this is you, contact us now. We can take care of your policy reviews and updating. Finally, you can get say “goodbye” to that makimaki on your back!

Learning from the Waitangi Tribunal Māori health report

The first report from the Waitangi Tribunal of its Kaupapa Inquiry into Māori health – Hauora – was released this month. It concluded that our primary health care system has failed to achieve Māori health equity; that New Zealand’s legislative, policy and administrative framework is not, in fact, fit to achieve this outcome.

News reports have highlighted the Tribunal’s findings of institutional racism. Here, we discuss some other aspects of the Tribunal’s report to help agencies give effect to some of the gems in the report (eg in their policies and practices).

We look first at the Tribunal’s approach to the Crown’s 3 Ps Treaty framework. We then look at new Treaty principles proposed by the Tribunal. Later, at some strategies for reflecting these principles.

The “3 Ps” – out with the old

The “3 Ps” comprise the well-established Crown Treaty framework – the principles of partnership, participation and protection. They came out of the Royal Commission on Social Policy in 1986.

The Tribunal described these principles as outdated and the Crown accepted that they reflect a “reductionist view” of the Treaty (Hauora, p79).

Thirty years on, with a lot more Treaty jurisprudence and Treaty settlements under our national belt, there’s clearly room to do better. The Tribunal proposes a new set of Treaty principles for New Zealand’s primary health care framework.

They are principles the Tribunal has relied on in a number of key reports (eg Te Whānau o Waipereira Report; The Napier Hospital and Health Services Report; Tū Mai Te Rangi! Report on the Crown and Disproportionate Reoffending Rates.) They are relevant to all sectors. We briefly outline them below by reference to the articles of Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

Tribunal treaty principles

Principle 1: Recognition and protection of tino rangatiratanga

This is guaranteed under Article 2 of Te Tiriti. It means that the right of Māori to organise in whatever way they choose – whānau, hapū, iwi or other form of organisation and to exercise autonomy and self-determination to the greatest extent must be recognised and protected.

Principle 2: Equity

This is an Article 3 Treaty commitment. It’s also about acting in good faith as a Treaty partner.

Equity is not just about allowing equal access to healthcare or other services for all. The Waitangi Tribunal highlighted that equity is also not just about reducing disparities. It involves the bigger goal of equitable outcomes for Māori.

The Tribunal approved the World Health Organisation’s definition “Equity is the absence of avoidable or remediable differences among groups of people, whether those groups are defined socially, economically, demographically or geographically.” (Hauora, p67)

Principle 3: Active protection

This principle is all about action and leadership. Devolution and permissive arrangements without Treaty leadership are not sufficient. Provision for equal opportunity or a “one-size fits all” approach also falls short.

The Crown must actively pursue and do whatever is reasonable and necessary to ensure the right to tino rangatiratanga and to achieve equitable health and social outcomes for Māori.

Principle 4: Partnership

Yes, this “P” remains. Its meaning reflects an interplay of articles 1 and 2 of Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

For the Crown to be a good governor it must recognise and respect the status and authority of Māori to be self-determining in relation to resources, people, language and culture (ie tino rangatiratanga). It must involve Māori at all levels of decision making.

Both the Treaty parties must act reasonably and in good faith towards each other.

Principle 5: Options

This principle is about giving real and practical effect to the principles of tino rangatiratanga and equity; articles 2 and 3 of Te Tiriti. Where kaupapa Māori services exist, Māori should have the option of accessing them as well as culturally appropriate mainstream services. They should not be disadvantaged by their choice.

It’s the job of the Crown to ensure each option is viable and sustainable by providing sufficient financial and logistical support, strong leadership and effective monitoring.

Report findings

The Tribunal concluded that the Crown had breached the Treaty in a number of ways. It found that from inception Māori primary health care organisations have been significantly underfunded, leading to a decline in the number of services. Whereas at a peak there were 14 Māori primary health organisations in the country, there are now only four (Hauora,p156).

A similar story of unrealised potential and breaches of the partnership and tino rangatiratanga obligations can undoubtedly be told in other sectors. For example, Iwi Social Services and Maatua Whangai were incorporated into the Childrens Young Persons and their Families Act (ie Oranga Tamariki Act) in 1989. They were established to play a key role in the statutory care system in response to Puao-Te-Ata-tu. However, they were undermined by a lack of resourcing and support (eg Shane Walker, Maatua Whangai o Otepoti Reflections -ANZASW).

The Tribunal report makes a number of recommendations. This includes two interim recommendations, that:

- an independent Māori statutory authority be explored

- the Crown and claimants work on a way of assessing the extent of underfunding of Māori primary health organisations and providers.

The parties must report back to the Tribunal on progress with these after 7 months.

Some learnings

There’s some great learning in the Tribunal report about giving effect to Te Tiriti o Waitangi. Some key points for organisations’ policies and practice are that:

- agencies should have a strong leadership focus on fulfilling Treaty obligations and achieving equitable outcomes for Māori

- feedback and data should be gathered about access and outcomes for Māori. It should be regularly reviewed, evaluated and used to support continuous improvement

- if you’re not making progress be wary of attributing blame to clients. Instead, consider different ways of delivering your service

- avoid deficit language “hard to reach”, “vulnerable children” that tend to individualise what are often structural or system issues

- consider and invest time, good faith and energy into building constructive treaty partnerships (with mana whenua, local Māori, tau iwi agencies)

- the Crown must ensure funding of kaupapa Māori services is sufficient for their viability and that mainstream services it funds are competent to provide services to Māori (ie staff and board are culturally competent)

- Māori are engaged at all levels of social and health sector decision-making from governance through to service delivery.

More to come

There’s more in this and other Waitangi Tribunal reports to learn from. Like other Tribunal reports its rich in opportunities to learn about Treaty compliance.

In another blog we’ll take a look at how the Social Sector Accreditation Standards- Level 2 and Core Health and Disability Standards line up with the Tribunal’s approach.

Get in touch with us if you’re wanting help with your policies and procedures. We love to hear from you.

Q and A Family violence information sharing

Changes to support information sharing about family violence are due to commence on 1 July 2019. Here’s some Q&As about what’s coming.

Q-Why is information-sharing being changed?

answer

Death reviews have shown missed opportunities to respond to family violence. The new information-sharing provisions aim to address this.

Q-Who’s affected?

answer

The new law applies to family violence agencies and social services practitioners. Both are defined broadly. Community services receiving government funding to help victims and/or to stop perpetrators of family violence, licensed early childhood services, schools and specified government agencies are included.

Q-What’s the change?

answer

There are some legal requirements. The gist of the changes is that if you’ve got information that could help another agency working with a person impacted by family violence then consider sharing it. It’s not compulsory to share the information but it is compulsory to consider sharing it.

This is important particularly for people working in health-related agencies who often feel conflicted about their duty of confidentiality versus sharing information.

Q–What happens if I share info?

answer

As long as you share information in good faith and are careful you wont be liable. You should check the relevance of the personal information requested or that you’re thinking about disclosing (eg is it relevant to a client’s assessment or plan?)

Q–What if a client doesn’t want to share their info?

answer

The point of the change is that safety rather than consent should drive information sharing.

Best efforts should be made to obtain a person’s consent to sharing their personal information and you should consider their views. But even if consent is withheld, you might decide the information should be shared eg to help with safety planning.

Q–What about a client’s trust?

answer

This is often a big worry. People trust us with information and we want to honour that trust. But the new law means we don’t have to put this above protecting a victim from violence.

We can still build and maintain trust. But it needs to be done from the start. Clients should be informed when welcomed to the service that personal information may be shared if it will help protect a victim of family violence. Transparency should then be maintained throughout the relationship when and if their personal information is shared for family violence reasons.

Q–What does it mean for policies?

answer

We’ve been updating our online policy service for members. Policies that are being updated include those dealing with privacy and planning.

We’ve had a lot of people join us lately, but it’s still a good time to join.

It takes about 8 weeks to get you online. But we’ll put you online with your policies updated. From then on, we regularly review them and keep them up-to-date.

Contact us if you need a hand.

Impact of youth-related reforms

What will be the implications of the youth-related changes in the Oranga Tamariki reforms? Now is the time to review your organisational policies if you want to get on board.

Today, I’m going to overview the changes. I consider how they address a key area of positive youth development – belonging – and the implications of the reforms for community and community services.

The Oranga Tamariki (OT) reforms.

The upcoming OT reforms establish new legislative principles and include age changes for leaving care, aftercare support and youth justice. The changes support positive youth development, in particular, “belonging” as a key developmental area for our youth.

Belonging in what sense?

The new legislation addresses three meanings of belonging for our rangatahi/youth:

- the tangible – physical spaces we occupy and to which we connect – home, turangawaewae, whenua, land, community, neighbourhood, country

- the relational – our membership and connections with whānau, family, hapū, aiga, peers and spiritual beliefs. This is the basis on which a young person can say “I am loved” (according to the Circle of Courage, a positive youth development approach)

- the restorative – recognising a feeling of belonging is essential to resilience, the ability to cope with life and pain and to recover from trauma, mental health and addiction issues.

New principles

The new principles of the Act will guide the Ministry in the exercise of its powers and functions. Some of them apply generally to children and young people and some are specific to young people involved in youth justice, and to youth who are 18 years and over transitioning from care.

A young person’s need to belong in tangible, restorative and relational senses is recognised and supported:

- young people should be increasingly supported to make their own decisions

- young people should be supported to address the impacts of harm

- the relationships between a young person and their family, whānau, hapū, iwi and family group should be supported and strengthened where appropriate

- their mana must be protected by recognising the young person’s whakapapa and respecting whanaungatanga responsibilities

- respect for a young person’s identity- gender, culture, sexuality, language, religion etc

- recognise and address barriers to inclusion and participation that can be faced by disabled children.

Raising age for youth justice

From 1 July, most 17-year-olds who offend will come into the Youth Court jurisdiction. This is a long overdue reform and will hopefully lead to further reforms enabling even older youth to be dealt with in the youth system in preference to adult courts.

The youth system, like the adult system, holds offenders to account. However, there’s more scope in the youth system for the tangible, relational and restorative aspects of belonging for a young person to be recognised and addressed. In other words, more scope for positive youth development.

Instead of having to appear in the adult courts, from 1 July, most 17-year-olds will be either diverted by police (as an Alternative Action) or, be referred directly to a family group conference before any charge can be laid against them. A family group conference has the potential to address a young person’s need for belonging: their tangible need for a place to call “home, and for trusting relationships to support them to take responsibility for wrongdoing, make amends and if appropriate, provide reparation to victims.

Age increase for leaving care and support for independence

The new legislation finally makes our country compliant with the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, making Oranga Tamariki the responsible parent it was always meant to be.

The care and protection system will apply to 17-year-olds. The reforms also provide a lot more support for rangatahi to transition from care to independence. A young person in care will be entitled to live with a caregiver up until age 21 and to access advice and assistance up until 25 years.

Oranga Tamariki already makes some provision for young people to be supported to transition from care. But the support to remain with a caregiver and provision for assistance until 25 years old are big shifts.

Supporting the young person’s path to independence is the kaupapa and addressing their need for belonging (in a tangible, relational and restorative sense) is crucial:

- maintaining their sense of home (tangible) with an existing caregiver

- supporting and building trusted relationships (eg whānau, aiga and others that exist)

- supporting the young person to address the impacts of harm

Implications for community and youth services

The changes are going to have a significant impact on OT itself. Funding for the changes was announced by the Minister of Children earlier this year.

Most youth services already work with rangatahi up to 25 years. But there may be impacts on these and other services, for example, more demand for:

- youth-friendly placements and care opinions

- health services to extend and open up to 17-year-olds (instead of making 18 the magic age for accessing a service)

- for iwi and others who are delegated to run FGCs

- for youth and other services who assist young people transitioning from care.

Buy-in from the community is crucial if these reforms are going to work. Rangatahi are part of families, whānau, hapū and family groups. It is at these levels therefore that the potential of the reforms to support young people’s sense of belonging and positive development has to be activated. Adequate resourcing and funding by government and local authorities for the community to do so is vital.

Review your organisational policies

If your organisation wants to be part of these changes it is a good idea to review your policies and procedures.

Some issues to consider include:

- your definition of a young person

- if you’re wanting to get on board with the extended youth justice jurisdiction, whether your policies adequately address legal obligations such as reporting and intersect with the court

- do the changes impact on your duty of care

- how you address youth participation

- whether your policies adequately support youth inclusive practice for the diversity of youth in this country

- the alignment of your policies and practices with the new legislative principles (general and specific youth principles).

Do you want policy help?

Contact The Policy Place if you need help with reviewing and updating your policies to support service provision to rangatahi. We want to awhi you in order to support some of our most disadvantaged young people. Let’s work together on this!