Employment

Policies and procedures for A&D recovery in the workplace

We need a recovery approach to alcohol and drug use as a society.

It’s been advocated in the criminal justice system so a health rather than a criminal approach would apply for drug and alcohol-related offending. (See, for example, He Waka Roimata pp 65-67; Rights, respect & recovery: alcohol & drug treatment strategy)

More recently, its been recommended by the Waitangi Tribunal as the preferred response to substance abuse and addiction issues of parents of tamariki involved in the statutory care system (see Tribunal Report: He Pāharakeke, he Rito Whakakīkinga Whāruarua).

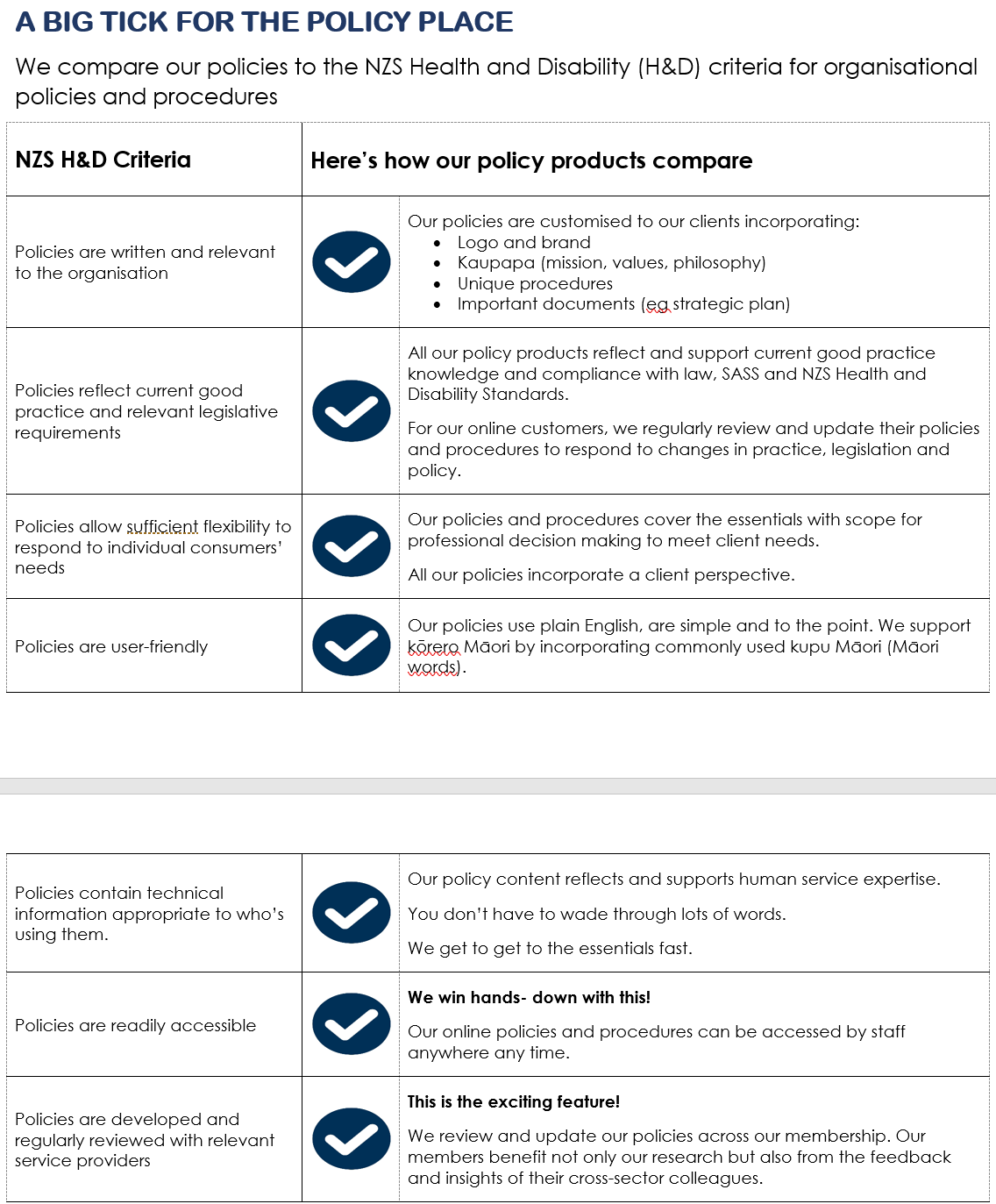

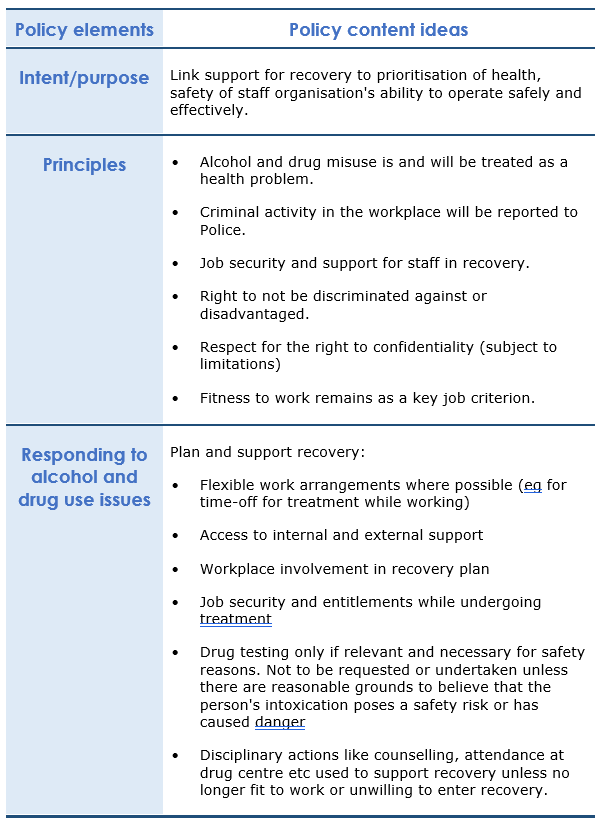

Making a difference with HR policies and procedures

We can all get behind this move to a recovery approach with our HR policies and procedures.

Too often, HR policies on alcohol and drugs in the workplace are narrowly framed around alcohol and drug testing and the consequences. They are usually punitive.

In the social and health services, we expect better of our client services. Alongside prohibiting drugs and alcohol we would also focus on recovery and support. So why not a similar approach in policies and procedures for staff?

Alcohol and drug testing may be important for safety- sensitive work. But there’s got to be more to it.

Our staffing policies need to be more balanced. They should outline if alcohol is allowed/not allowed in the workplace and the consequences of being intoxicated while at work alongside policy and procedure aimed at:

- preventing and educating staff about alcohol and drug use in the workplace

- supporting staff to speak up early if they have concerns about their drinking or drug use, and

- supporting staff with recovery.

Below, we give some ideas to help get you started with new or revised policy and procedure content on alcohol and drug use in the workplace.

Contact us if you want help with this or other policies and procedures. We provide balanced and humane policies.

For social and health services, our most popular service is the online policy and procedure service. It includes regular reviews and updates of policies. It means you don’t miss opportunities to support new or different approaches to hard issues like alcohol and drugs through your workplace policies and procedures.

Risky business – when offending hits the workplace

The case of Philip Barnes was recently laid bare in New Zealand media when his name suppression order was lifted. It’s a good reminder about what not to do when, as a manager, you learn that a staff member may have been involved in offending.

The case

In 2017, International Accreditation New Zealand (IANZ) management learned that Barnes (a General Manager) was involved in a Police investigation of spying in a gym changing room. Police uplifted Barnes’ computer from IANZ and returned it a few days later.

In June 2018, Barnes pleaded guilty to making an intimate visual recording. He sought and got name suppression. In 2020, he was discharged without conviction and granted permanent name suppression. Both orders were successfully appealed by Police and recently, the name suppression order was lifted.

While Barnes was being investigated by Police, IANZ conducted an investigation. A minimal investigation. They questioned Barnes and accepted his assurances that he was involved, basically, as “someone in the wrong place at the wrong time.”

3 lessons

Don’t turn a blind eye

In this case, offending occurred outside work. Even so, as a manager, you can’t assume that the offending will not impact on the business.

An employee’s conduct outside of work may bring an agency into disrepute. This was clearly a risk for IANZ.

Turning a blind eye, by accepting Barnes’ explanation for the Police investigation without checking objective facts, exposed IANZ to significant risk.

Even if offending is alleged to have occurred outside work, as a manager, it’s important that you make reasonable inquires to apprise yourself of the facts.

You don’t have to duplicate the Police investigation. It’s important not to interfere with it.

But it is important that you make sufficient inquiry to fully understand the nature and possible consequences of the allegation(s) to your staff, organisation and client base.

Don’t assume innocence or guilt

We all want to believe the best of people, particularly of staff who we work beside each day and we know to be hardworking. Conversely, we may be more inclined to think a staff member is guilty if we don’t like them.

Either way, hold off. Resist any such assumption.

Your best bet is to be as dispassionate as possible about the allegation(s), while being compassionate and fair to the staff member concerned and any affected staff or others. This will enable you to undertake a reasonable and balanced inquiry into the nature of the allegation(s) and scope the risks associated with them.

Assess and manage risk

The major omissions in the IANZ/Barnes case were the failure to make a reasonable inquiry into the Police investigation. Secondly, IANZ failed to fully scope, assess and manage risks, including risk to its reputation as an agency that’s all about upholding standards.

Risk assessment and management are key tasks for management when confronted with alleged offending by an employee.

Risks to the victim(s), staff member, clients, colleagues, and to the reputation of the agency must all be assessed.

Mitigations established as necessary. They might involve suspension, a change of duties, extra supervision, change of workplace or work hours, etc – depending on the situation, level and nature of risk(s). Mitigations need to be worked out with the employee concerned and their effectiveness monitored and adjusted accordingly.

So…

Learn from what IANZ didn’t do.

Review your policies and procedures to make sure they guide you and your staff to respond if staff become involved in a Police investigation.

At the Policy Place we’ve got you covered if you’re a member of our online policy service. Risk management is an important feature of our online policies eg policies on Background and Child Safety Checking, Quality Assurance, Service delivery and Health and Safety.

If you want to know you’re covered with good policies that are reviewed and kept up-to-date contact us to join the online policy service or book a free consultation to talk about your needs.

The wrong and right of criminal history checking in your policies and procedures

Systemic bias is part of the criminal justice system and disproportionately impacts on Māori and people with disabilities. It contributes to many, long term health, income and educational disparities.

Organisational policies and procedures that ban outright the employment of people with criminal histories reinforce and perpetuate this bias. They are unfair and should be replaced.

Legal constraints

Yes, there are legislative constraints. Social, health and education services in Aotearoa are bound by the Children’s Act 2014, associated regulations, accreditation and licensing requirements.

These rules require safety checking by “specified organisations” like social services, health services, schools and early childhood centres. This involves police vetting and gathering a range of other personal information from referees and others. Risks indicated through the process must be assessed.

But these rules do not necessitate a general employment ban against people with criminal pasts.

The only provision that comes close to a general ban is the rule for criminal histories involving sexual violence or violence against children (ie offences listed in Schedule 2 of the Children’s Act).

No organisation covered by the Children’s Act may lawfully employ a person as a core children’s worker if they have committed one of these offences unless an exemption is obtained. The exemption process is administered by MSD.

So while there are restrictions, there is no legislative mandate for organisational policies and procedures to totally ban the employment of people with criminal histories.

There is also no mandate for a complete ban in policies and procedures against “dishonesty” and “violent” offences. Dishonesty and violence are broad-ranging terms that encompass a wide range of offences. “Violent” offences potentially include minor acts and threats of assault through to much more serious offences against the person. “Dishonesty” likewise covers the $5.00 theft through to deliberate and long term fraud.

Due diligent approach

A fairer and more humane approach, consistent with legislation, is for policies and procedures to prescribe a due diligence approach. This involves gathering the information required under law and identifying any risks. If there are risks, assessing the level and likelihood of risk and whether and how the risks can be managed in the workplace.

Policy and procedure should also prescribe kōrero/talking with the person concerned about the risks and agreeing and monitoring a risk management plan.

On this approach, a criminal record for dishonesty may mean that the person concerned should not be recruited into a rule involving the handling of money. But that same person may be considered for another type of job in the organisation. Likewise, an offence involving violence committed while under the influence of drugs may not preclude a person from being employed as a youth worker if there is evidence they are in recovery.

Give it a go

Recruitment involves big decisions that have long term impacts. We want to get it right. It’s tempting to set up no-go zones like criminal histories to try and make the decision process “safer”.

But these exclusions are unfair and unjust. They cause organisations to miss out on a pool of skills and experiences that they and their clients could benefit from.

With a due diligent approach, a person with a criminal history may end up being excluded from employment. But this will reflect a fulsome consideration of the person’s skills, experience and past, a far more reliable exercise then simply excluding them.

The person’s right to be treated with dignity and given the chance to move on from their past will also have been respected.

So give it a try. Review and update your policy and procedure on background checks. If you want help with this or any other organisational policies and procedures, contact us NOW.

Your guide to child and family-friendly policies and procedures

Heart, mind and skills are essential, but policies and procedures are also important. They set base-lines for child and family-friendly practice in an agency.

Here’s a checklist of some key policies and procedures to support child, whānau and family-friendly practice in your agency.

Contact The Policy Place for help with these and other policies and procedures.

|

Flexible working arrangementsIt’s in the Employment Relations Act but policy and procedure helps clarify:

|

|

Tamariki in the workplaceTo evidence compliance with Social Sector Accreditation Standards – Level 2 policies and procedures should clarify roles and responsibilities for tamariki while on-site, provide for adequate supervision and use of child safe practices. |

|

Address diversity amongst rangatahi and familiesPolicies and procedures should:

|

|

Inclusion and engagement of children and whānauBoth Social Sector Accreditation Standards and Health and Disability Standards require mahi and engagement with families. Policies and procedures can help clarify how this should be done in:

Policies to recognise and support children’s rights to participate in services and decisions that relate to them are a must for Social Sector Accreditation Standards (eg policies for informed consent, feedback and complaints). |

|

Evaluation and ongoing improvementFeedback and complaint policies should provide for feedback and complaints from family members about their service experience. They must be age and stage appropriate for tamariki with different abilities. |

|

Support whānau ora/ family wellbeingPolicies and procedures should address:

|

|

Best interests and protection of tamariki/rangatahiPolicies and procedures for social, health and disability services must address:

It’s also helpful for agencies to have policies and procedures in place about how challenging behaviours should be managed, the use of child-safe practices and how children’s safety and best interests will be prioritised. |

|

Background and child safety vettingPolice vetting and child safety checks for children’s workers are a must under the Children’s Act 2014. |

Performance assessment

Pink Shirt policy

With pink shirt day on Friday, we’re reminded of the harms of bullying. We must be proactive and respond when bullying occurs in the workplace, at school or another area of life.

Everyone needs a bullying policy…

To help set some ground rules for safety and conduct, every organisation should have a harassment and bullying policy. Here’s what we think are some essentials for a bullying policy:

- the intent of the policy should be clearly stated eg wellbeing at work, that bullying is not tolerated, bullying complaints are dealt with fairly, protection of rights.

- bullying is defined to include conduct that is intimidating and unwelcome. Important here is that bullying can be intentional or unintentional. Conduct may be through texting, emails, social media etc.

- the steps that can be taken if and when bullying occurs must be spelt out. A complainant’s wishes and their right to safety should be central. Due process for a respondent must also be observed. In some situations, there may be opportunity for complaint through an external body eg Human Rights Commission or Netsafe. These avenues should be included in your policy.

- prevention strategies and the obligation to build a culture of respect and tolerance should be also be covered. This is the proactive part. It’s what everyone must take ownership of in the workplace.

A bullying policy must apply across the organisation – to governance, management, staff and volunteers. The policy should require the organisation’s leaders and governors to champion a culture of respect and tolerance, ensure a fair and timely follow up on complaints and to model that bullying, under any pretence (eg stress, anxiety, fun) is not ok.

We can help!

Bullying and harassment is covered in our core set of policies at the Policy Place. Join up to our online service so all of your staff can access the latest in policy development. Online access is a great way to get everyone on the same waka going in the right direction – so important when it comes to providing safe and tolerant workplaces.

Give us a ring at the Policy Place to discuss your policy needs and find out more about how we can assist.

Domestic Violence

Domestic violence has wide ranging impacts on the lives and opportunities of those it affects. From April this year, workplaces will be required to play their part in supporting domestic violence survivors. Are your policies and procedures going to be ready?

The Domestic Violence – Victims’ Protection Act 2018 commences on 1 April 2019. We are reviewing our members’ policies and procedures and will be updating them in readiness (look for our Policy release in March!).

The Act addresses the impact of domestic violence on a person who is in employment or to a child of the employee. It uses the domestic violence definition contained in the Domestic Violence Act which, in July 2019, will be replaced by a definition of family violence.

The Act entitles an employee to request a short term variation of employment terms to deal wtih the impact of domestic violence regardless of how long ago the domestic violence occurred and even if the domestic violence occurred before the person became an employee.

The Act also establishes entitlement to domestic violence leave up to 10 days.

There are a number of consequent obligations on employers.

A staff member affected by domestic violence must not be adversely treated by an employer for this reason. If adverse treatment occurs, the staff member will have a right to pursue a personal grievance.

Members already have family violence policies and procedures in place for staff and clients. The new legislation applies to the workplace.

We have assessed it will require only minimal change to staffing policies and procedures. Our existing policies support workplace awareness about family violence and responses to safety and support concerns. This will remain the focus but we will strengthen provision for leave and variation of employment terms to comply with the new legislation.

Contact us at the Policy Place for help with reviewing and updating your policies and procedures to comply with the new legislation and other upcoming changes.