Organisational Policy and Procedures

Performance assessment

Are you missing out? Is good policy what you need?

Are you missing out on the benefits of having good up-to-date policies and procedures? In this post, we look at the value of good policy and procedures for organisations of all types.

If you want to get more out of your operating expenses and want more time to spend on other things, then read on.

Policies are multi-functional

Organisational policies and procedures are not just about compliance. They are multi-functional:

- They are like a will. They help avoid the chaos and distress of uncertainty about what to do about a situation.

- They double as a how-to guide for staff when faced with new responsibilities, roles and challenges.

- If you’re expanding into new areas or building new collaborations, policies and procedures can be used to reflect agreement on the important stuff like communication, reporting, information-sharing, expenditure and income allocation.

- They help you manage risks, for example of litigation, penalties, health and safety issues and risks to reputation.

Great bang for your buck. Yet, so many organisations and businesses are not reaping these benefits.

Danger

Too often organisations’ policies and procedures sit in old electronic and paper files, pulled out just for audits then put away again.

To state the obvious, this is dangerous! It’s a bit like not maintaining the structure of your house or whare. Eventually, rot can set in and more damage occur.

Unfortunately, we hear of lots of such calamities. Some publicly-aired ones include:

- injuries in childcare centres where there was no policy and procedure to guide action and as a result, errors were made;

- injury to a person being transported by an agency without sufficient safeguards in place;

- abuse perpetrated against children and disabled people in residential settings where processes for reporting concerns were inadequate; and

- a failure to provide adequate medical treatment where there was no policy and procedure on informed consent and client-centred practice.

Time waster

Without good organisational policies, you’re also likely to be wasting a lot of needless time and energy, for example:

- repeatedly telling staff what to do and having them tell you that they don’t know what to do

- dealing with complaints

- solving recurring problems with ad-hoc responses

- doing fix-its on solutions that were made up by staff because they couldn’t access good guidance.

It’s wasted time; time that could be better spent on yourself or whānau or on other organisational priorities.

What’s good organisational policy and procedure?

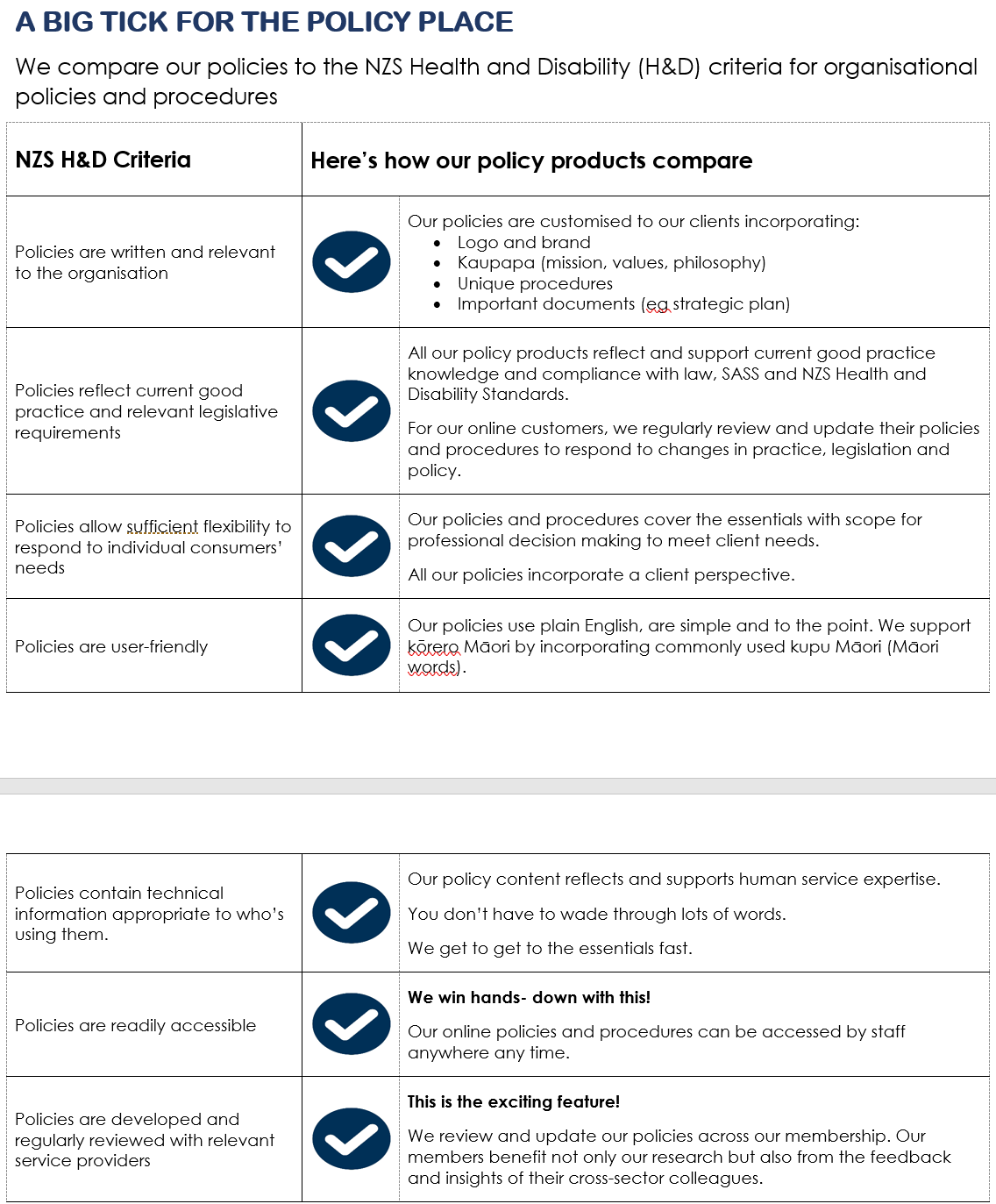

To help figure out what state your policies and procedures are in, consider the criteria for policies and procedures in the NZS 8134.1: 2008 Health and Disability Services Standards. Standard 2.3 requires policies and procedures to:

- align with current good practice and service delivery

- meet legislative requirements

- be reviewed regularly

- be supported by a document control system to ensure that old versions of policies are not being used.

Guidance for NZS 8134.3.1:2008 recommends additional criteria; that policies and procedures should:

- be written and relevant to the organisation

- be sufficiently flexible to respond to consumer needs

- have a user-friendly format

- contain appropriate technical information

- be accessible to all staff

- be developed and regularly reviewed with relevant service providers

- identify helpful links (ie to other documents)

See here for how the Policy Place online policy and procedure service measures up.

Where to start

The task of reviewing and updating policies and procedures can feel overwhelming. It can be hard to know where to start.

If you’re into the DIY approach, as a first step get updated on legislation changes. Take a look at our post outlining key legislation changes over the last year. At the very least you will need to review and update your policies using the legislation and the standards with which you much comply (ie SASS or HD stds.) Involve staff, research and reflect good practise literature.

Let us handle it

You can let go of the stress and give us the job to do. At the Policy Place we are reviewing and updating organisations’ policies and procedures all the time. You get the benefits of policies and procedures that reflect cross-sector knowledge of good practice and policy and procedure expertise.

We give you policies and procedures fit for the 21st century with our online service. We keep them updated and regularly reviewed so you, your board and staff, have a lot less to worry about and a lot more time and energy for the things you want to do (eg recreation and leisure, other work priorities).

Book your free policy consultation

Email us about your policy and procedure needs.

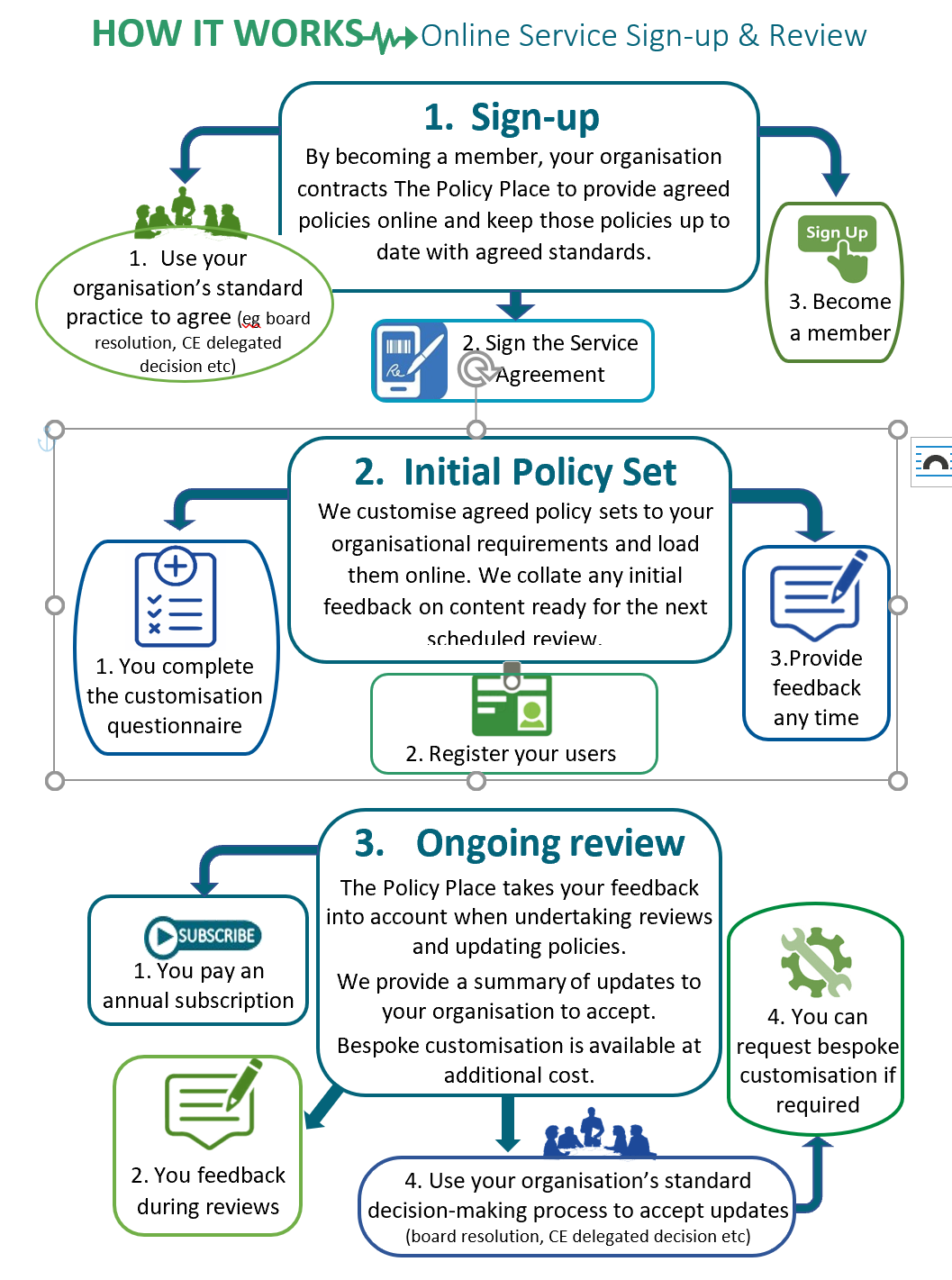

Online policies and procedures – so easy!

Kia mauriora te reo Māori

Could you achieve 85 per cent of your staff and board valuing te reo Māori? Did you know we have a new Māori language strategy to achieve that as a nation? Already achieved that goal? Consider a language plan to support 85% of your staff and board to speak te reo Māori.

We all have a role in the revitalisation of te reo Māori. We all have much to gain.

This was a key message in the Waitangi Tribunal’s 1986 Report on Te Reo Māori claim and more recently in its Ko Aotearoa Tenei report.

It’s a message that is now reflected in the principles of Te Ture mō Te Reo Māori 2016/ the Māori Language Act 2016. The principles of the Act include that te reo Māori:

- has inherent mana and is enduring

- is the foundation of Māori culture and identity

- enhances the lives of iwi and Māori

- is protected as a taonga under Article 2 of the Treaty

- is important to our national identity.

The Government recently launched its new Māori language strategy under this Act. It reflects these new legislative principles and responds to long-time calls for the language to be protected as a taonga and revitalised.

So what does all of this mean for those of us working outside government? In this post I look at what we can do to support the revitalisation of the reo.

Maihi Karauna

This is the government’s new strategy to revitalise the reo. It replaces the previous Māori language strategy, which was strongly criticised by the Waitangi Tribunal for being deficient and contributing to a decline in the use of te reo Māori (Ko Aotearoa Tenei, pp 165-7).

Maihi Karauna was developed as a partnership between the Crown and iwi and Māori (represented by Te Mātāwai). It provides for:

- Te Mātāwai to focus on homes, communities and the nurturing of tamariki Māori as first language speakers of te reo Māori. Whānau, hapū and iwi are a vital part. See here for Te Mātāwai’s Maihi Māori/ Māori strategy

- the Crown to create and foster societal conditions where te reo Māori is valued and in partnership with Te Mātāwai, develop policies and services that support language revitalisation.

Goals

Maihi Karauna sets some “audacious” goals. By 2040:

- 85 per cent of kiwis (or more) will value te reo Māori as a key part of national identity

- at least 1,000,000 New Zealanders will be confident talking about at least basic things in te reo Māori

- 150, 000 or more Māori aged 15 and over will use te reo Māori at least as much as English.

Tracking progress

Unlike the previous Māori Language strategy, Maihi Karauna sets indicators for measuring progress towards these goals. The plan is to implement it progressively, starting with the current “establishment phase” (for more on implementation planning see here.)

What can we do?

Maihi Karauna requires each of us to step up and nurture and promote te reo Māori as the indigenous language of Aotearoa.

To date, it has been largely Māori who have fought for the survival of the language. Broader support is required. As people working with whānau, rangatahi and adults, social and health organisations can play a key part.

What about a language plan?

As part of implementing Maihi Karauna, public sector organisations will be expected to have language plans in place by 2021. A language plan could also be a good start for agencies and businesses wanting to give more priority and focus to the language. Think about how to engage with your staff, the expertise of Māori speakers on staff and obtain cultural advice about local tikanga and reo, for example, from mana whenua and local Māori/iwi services.

Review and update relevant policies and processes

It ‘s timely to review your policies on Te Tiriti o Waitangi and Diversity and inclusion. Consider if changes should be made to better support te reo in your organisation. For example, consider:

- supporting and requiring staff and volunteers to pronounce kupu Māori correctly, particularly the names of people and places and frequently used phrases

- incentives for staff to commence or further their learning of te reo

- how te reo me nga tikanga (cultural practices) are used in the organisation’s day-to-day practices

- increasing access to cultural supervision and cultural advice

- making the reo more visible in the organisation (eg signage, labels)

- promoting reo initiatives such as Māori radio, tv and social media channels

- recognise and remunerate Māori language speaking as a core competency for staff

- support national promotions of te reo (eg Te Wiki o te reo Māori).

Any or all of these should be included in your policies and procedures.

Conclusion

So there’s a lot we can and should be doing. There’s no need to feel overwhelmed. Every small step counts.

In Ko Aotearoa Tenei (p166), the Waitangi Tribunal referred to an old Māori proverb :

“Mā te huruhuru, te manu ka rere” which means birds can fly only with feathers.

Let’s all be part of enabling te reo Māori to soar.

Kia Kaha Te Reo Māori!

Words for people not processes!

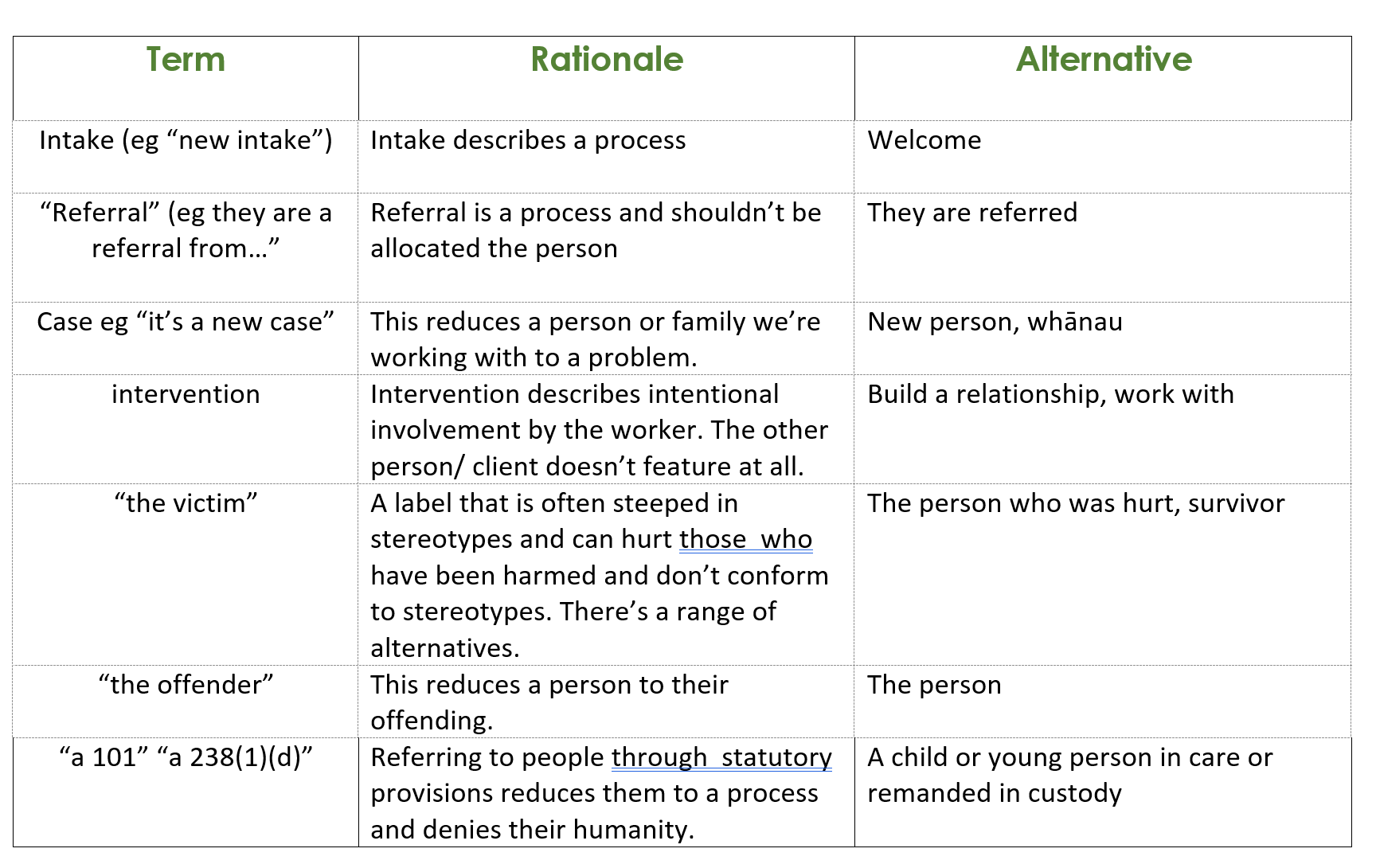

Hōkai Rangi – the new Corrections Strategy 2019-2024 – sets out an awesome kaupapa/vision for Corrections in the future. It also reflects on problems in the current system.

Language is one of the problems. Some terms commonly used in the corrections system are dehumanising eg “muster.” It reminded me that some language we use in the social sector can be equally problematic.

At the Policy Place, we want our policies and procedures to support people – centred practice in health and social services. Here’s some terms we’ve identified as problematic, some alternatives and why.

What do you think?

What terms are used in social and health services that you think are problematic? Let us know along with what you think are good alternatives. We’ll add your terms to the list below to help us all become more conscious and agile with people-focused language.

Get that makimaki/monkey off your back

There’s been a lot of change in law, policy and practice recently affecting social, health and disability services. There is likely to be more.

In this post, we overview some key changes to consider when reviewing and updating your organisation’s policies and procedures.

If policy review and updating feels like a makimaki/monkey on your back, contact us now for help. You can schedule a free 30 minute consultation about your needs and your best policy solution. We can take care of the reviews and updating.

If you’re a DIY policy person, tick off these changes as you review your organisation’s policies and procedures.

Legislation changes

Key changes that have commenced this year have been:

- new provision for family violence leave and variation of employment terms for staff affected by family violence

- changes to the law relating to family violence including how and when family violence information can be shared between authorised services and persons

- changes relating to information-sharing for child protection and wellbeing purposes

- extension of Oranga Tamariki legislation (statutory care and youth justice) to under 18 years (was previously up to 17 years)

- more support for young people leaving statutory care or custody up to 25 years

- new principles to guide decisions and interventions under the Oranga Tamariki legislation (eg addressing mana tamaiti, recognition of whakapapa and involvement of those with whanaungatanga responsibilities)

- new requirements on the CE of Oranga Tamariki to enter strategic partnerships with iwi, to give practical effect to Te Tiriti o Waitangi and to report and monitor performance on outcomes for tamariki Māori

- the introduction of new care standards setting minimum requirements for the statutory care of tamariki.

Practice

And don’t forget relevant practice and sector developments that are important enough to incorporate into your policies and procedures, for example:

- stronger recognition across sectors of whānau-centric practice

- more recognition of the need for trauma-informed responses

- move from 3 Ps Treaty framework to article-based framework

- more focus on workplace health and wellbeing

- focus on cultural safety and cultural competency

- mainstreaming – equality and accessibility

- individualised funding.

Quit feeding the makimaki!

Usually, people contact us because they know their policies and procedures are not up to date. They are busy managing services like social housing, family violence intervention, care, mental health, counselling, perpetrator programmes, family support, sexual violence services etc.

They haven’t got the time to keep their organisations’ policies and procedures up-to-date. They no longer want the worry of it.

If this is you, contact us now. We can take care of your policy reviews and updating. Finally, you can get say “goodbye” to that makimaki on your back!

It’s cool to kōrero te reo Māori Kūki Āirani!

Kia orana, Turou, ’āere mai ki te ‘epetoma o te reo Māori Kūki’ Āirani. Welcome to Cook Island Language Week. The theme of the week is “Taku rama, taau toi: ora te Reo” – “My Torch, Your Adze: The Language Lives.”

In honour of the week, this post uses words of te reo Māori Kūki Āirani/ Cook Island Māori language.

It’s a good time to reflect on how our agencies respect and support te reo Māori Kūki Āirani and other Pacific languages; how we ensure culturally responsive services to Pacific people. The two are linked. Reo (language) reflects respect for peu (culture) and respect for culture is directly relevant to service access and quality.

As we outline below, Pacific peoples and their culture have a special place in Aotearoa. This reflects in accreditation requirements and should accordingly reflect in organisational policy.

Respect for pacific

Pacific peoples comprise 8% of the population. The population includes a range of ethnicities, languages and communities, those born overseas and those born in Aotearoa who culturally identify with a pacific identity. Charities Services data shows there are 500 Pacific not-for-profit organisations in the country, with churches making up the majority of these (NZ Treasury, The New Zealand Pacific Economy, 13 November 2018) .

Samoan is the largest Pacific population in the country. The Cook Island population is the second-largest. Te reo Māori Kūki Āirani comes from the same language group spoken by Māori, Tahitians and Hawaiians. There are more Cook Island Māori living in NZ than there are in the Cook Islands (See Ministry for Pacific Peoples, Cook Islands Language Factsheet).

We are a Pacific nation and have a special relationship with Pacific islands. The relationship has been chequered at times, eg the targetting of Pacific peoples in “dawn raids” – a “shameful passage” in New Zealand’s race relations”.

Both this history and the importance of our connection to other Pacific islands within the “sea of islands” (coined by famous Tongan author Epeli Hauʻofa) reflect in accreditation requirements for social, health and disability services.

Accreditation requirements

Both the Social Sector Accreditation Standards – Level 2 and NZS Health and Disability Standards require that services recognise and respect Pacific cultures, values and beliefs and that services are carried out in a culturally competent and culturally safe way.

This may be demonstrated in a number of ways, one of which should be through organisational policy.

The value of a good organisational policy

Good organisational policy and procedure that is user-friendly (for staff and volunteers) provides the opportunity to communicate some minimum requirements about culturally safe and culturally competent practices and to achieve consistency within your organisation about this. It is a good way of reinforcing the importance of cultural safety and cultural competence to staff and volunteers.

Ingredients

How and what you provide in the policy and procedure will depend on factors such as:

- whether you are a Pacific or mainstream service

- your practice framework

- your kaupapa

- the services you provide (eg direct services, advocacy).

Organisations will have their own views on what they consider important enough and appropriate to enshrine in policy. If you’re not a Pacific agency, it will be helpful to consult with your Pacific staff, volunteers and clients and those you network with about what they think should be in your policy.

Some things to think about are:

- a process for staff obtaining cultural advice and preparing for engagement with Pacific clients

- promoting and using pacific languages to facilitate access to the service and express respect

- staff training (eg awareness of own cultural framework and assumptions; importance of ngutu’are tangata (family), use of pacific models of health and wellbeing)

- referral pathways to provide people with the choice of accessing Pacific or mainstream agencies

- collection and monitoring of data about ethnicity of people accessing the service and achievement of pacific aims

- feedback and improvement strategies (eg a Pacific plan)

Conclusion

In te ‘epetoma o te reo Māori Kūki’ Āirani, it’s good to reflect on Pacific connections and how we’re going in delivering culturally safe services to Pacific peoples.

Through our policies, we signal what we regard as important to our organisation. The right of Pacific peoples to culturally respectful and responsive services is important enough for policy.

Contact us

Give us a ring if you need help with your policies and procedures. We love our mahi and talking to people about their diverse policy needs. Alternatively, take a look at our policy products to find out what we offer.

For more information about te reo Māori Kūki Āirani see the Ministry for Pacific People’s fact sheet and educational language resource.

Learning from the Waitangi Tribunal Māori health report

The first report from the Waitangi Tribunal of its Kaupapa Inquiry into Māori health – Hauora – was released this month. It concluded that our primary health care system has failed to achieve Māori health equity; that New Zealand’s legislative, policy and administrative framework is not, in fact, fit to achieve this outcome.

News reports have highlighted the Tribunal’s findings of institutional racism. Here, we discuss some other aspects of the Tribunal’s report to help agencies give effect to some of the gems in the report (eg in their policies and practices).

We look first at the Tribunal’s approach to the Crown’s 3 Ps Treaty framework. We then look at new Treaty principles proposed by the Tribunal. Later, at some strategies for reflecting these principles.

The “3 Ps” – out with the old

The “3 Ps” comprise the well-established Crown Treaty framework – the principles of partnership, participation and protection. They came out of the Royal Commission on Social Policy in 1986.

The Tribunal described these principles as outdated and the Crown accepted that they reflect a “reductionist view” of the Treaty (Hauora, p79).

Thirty years on, with a lot more Treaty jurisprudence and Treaty settlements under our national belt, there’s clearly room to do better. The Tribunal proposes a new set of Treaty principles for New Zealand’s primary health care framework.

They are principles the Tribunal has relied on in a number of key reports (eg Te Whānau o Waipereira Report; The Napier Hospital and Health Services Report; Tū Mai Te Rangi! Report on the Crown and Disproportionate Reoffending Rates.) They are relevant to all sectors. We briefly outline them below by reference to the articles of Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

Tribunal treaty principles

Principle 1: Recognition and protection of tino rangatiratanga

This is guaranteed under Article 2 of Te Tiriti. It means that the right of Māori to organise in whatever way they choose – whānau, hapū, iwi or other form of organisation and to exercise autonomy and self-determination to the greatest extent must be recognised and protected.

Principle 2: Equity

This is an Article 3 Treaty commitment. It’s also about acting in good faith as a Treaty partner.

Equity is not just about allowing equal access to healthcare or other services for all. The Waitangi Tribunal highlighted that equity is also not just about reducing disparities. It involves the bigger goal of equitable outcomes for Māori.

The Tribunal approved the World Health Organisation’s definition “Equity is the absence of avoidable or remediable differences among groups of people, whether those groups are defined socially, economically, demographically or geographically.” (Hauora, p67)

Principle 3: Active protection

This principle is all about action and leadership. Devolution and permissive arrangements without Treaty leadership are not sufficient. Provision for equal opportunity or a “one-size fits all” approach also falls short.

The Crown must actively pursue and do whatever is reasonable and necessary to ensure the right to tino rangatiratanga and to achieve equitable health and social outcomes for Māori.

Principle 4: Partnership

Yes, this “P” remains. Its meaning reflects an interplay of articles 1 and 2 of Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

For the Crown to be a good governor it must recognise and respect the status and authority of Māori to be self-determining in relation to resources, people, language and culture (ie tino rangatiratanga). It must involve Māori at all levels of decision making.

Both the Treaty parties must act reasonably and in good faith towards each other.

Principle 5: Options

This principle is about giving real and practical effect to the principles of tino rangatiratanga and equity; articles 2 and 3 of Te Tiriti. Where kaupapa Māori services exist, Māori should have the option of accessing them as well as culturally appropriate mainstream services. They should not be disadvantaged by their choice.

It’s the job of the Crown to ensure each option is viable and sustainable by providing sufficient financial and logistical support, strong leadership and effective monitoring.

Report findings

The Tribunal concluded that the Crown had breached the Treaty in a number of ways. It found that from inception Māori primary health care organisations have been significantly underfunded, leading to a decline in the number of services. Whereas at a peak there were 14 Māori primary health organisations in the country, there are now only four (Hauora,p156).

A similar story of unrealised potential and breaches of the partnership and tino rangatiratanga obligations can undoubtedly be told in other sectors. For example, Iwi Social Services and Maatua Whangai were incorporated into the Childrens Young Persons and their Families Act (ie Oranga Tamariki Act) in 1989. They were established to play a key role in the statutory care system in response to Puao-Te-Ata-tu. However, they were undermined by a lack of resourcing and support (eg Shane Walker, Maatua Whangai o Otepoti Reflections -ANZASW).

The Tribunal report makes a number of recommendations. This includes two interim recommendations, that:

- an independent Māori statutory authority be explored

- the Crown and claimants work on a way of assessing the extent of underfunding of Māori primary health organisations and providers.

The parties must report back to the Tribunal on progress with these after 7 months.

Some learnings

There’s some great learning in the Tribunal report about giving effect to Te Tiriti o Waitangi. Some key points for organisations’ policies and practice are that:

- agencies should have a strong leadership focus on fulfilling Treaty obligations and achieving equitable outcomes for Māori

- feedback and data should be gathered about access and outcomes for Māori. It should be regularly reviewed, evaluated and used to support continuous improvement

- if you’re not making progress be wary of attributing blame to clients. Instead, consider different ways of delivering your service

- avoid deficit language “hard to reach”, “vulnerable children” that tend to individualise what are often structural or system issues

- consider and invest time, good faith and energy into building constructive treaty partnerships (with mana whenua, local Māori, tau iwi agencies)

- the Crown must ensure funding of kaupapa Māori services is sufficient for their viability and that mainstream services it funds are competent to provide services to Māori (ie staff and board are culturally competent)

- Māori are engaged at all levels of social and health sector decision-making from governance through to service delivery.

More to come

There’s more in this and other Waitangi Tribunal reports to learn from. Like other Tribunal reports its rich in opportunities to learn about Treaty compliance.

In another blog we’ll take a look at how the Social Sector Accreditation Standards- Level 2 and Core Health and Disability Standards line up with the Tribunal’s approach.

Get in touch with us if you’re wanting help with your policies and procedures. We love to hear from you.

Consent and mandated clients

Informed consent is a human right. But honouring it for clients who are mandated by a court or statutory agency can be a challenge. We look here at how your organisational policy on informed consent can be helpful.

Is this you?

Your organisation has a policy on consent. It has never been an issue because you have always worked with voluntary clients.

But things have changed.

You are now funded to deliver a response to offending, family violence or other problem that used to be dealt with by formal statutory or court intervention. The alternative for the client, as the context for their engagement with you, was a formal or worse intervention (eg conviction, or prison).

What does this mean for your organisational policy on consent?

In these circumstances, consent is undoubtedly compromised. Yet you are required by the Social Services Accreditation Standards and Public Health and Disability Standards to have policy and procedures to ensure all clients (whether mandated or not) exercise their right to informed consent.

So what should your organisation’s policy provide and is there potential for it to help transform an involuntary and unequal situation into more of a voluntary one? YES. A good informed consent policy can help guide empowering practice and authentic engagement with clients. Here’s what we see as some key elements of this type of policy.

Consent is a process

Your policy needs to recognise that there are multiple points in the relationship with a client where consent can be sought. Each of these points offers the client the chance to re-assert their rights to autonomy and make decisions for themselves; to help equalise the situation.

While a person should be asked to consent when they enter a service, this should not be with carte blanche effect. It should only mark the beginning of the consent process. Your policy should require that consent is sought at every key point of involvement with the client. It should be supported and reinforced by other policies addressing client/whānau rights to participate and person/whānau centred responses.

Culture matters

In the Anglo world, certainly in the liberal western tradition of thought, consent is seen in individualistic terms. But that’s just one perspective. Both the significance and process of giving consent can vary cross-culturally and this needs to be recognised in your policy. Important policy requirements include accessing cultural advice and asking the client about their expectations for giving consent. Where collective cultural values are important, the consent process may need to allow for time and the participation of whānau and others.

Be real

Acknowledging the constraints on a client’s choices is important. It’s essential for building an open and honest relationship with a client/whānau. It’s integral to empowering the client within the consent process.

A consent policy should therefore require kōrero with the client about the reasons and conditions of the referral and consequences of non-compliance with those conditions. And don’t forget to cover your agency’s role and responsibilities.

You must explain to the person ordered to attend a Family Violence Perpetrator programme or a young person attending your service as part of their Supervision with Activity order that your agency will have to report to the court/Oranga Tamariki if they don’t comply with the terms of service and likelihood of a court-imposed sanction.

Inform, inform

The Health and Disability and Social Services Accreditation Standards require informed consent. This means providing the full raft of information that a client needs to make their decisions and giving accurate and balanced information. Options should be canvassed and the consequences of giving or refusing consent (e.g risks, benefits, costs). The client should be encouraged to ask questions on the basis there are no silly questions

We all need support

The last but probably one of the most important policy requirements is that we should assume a client will need support to give consent. We work with clients often in mental distress or dealing with conditions or circumstances that can diminish their capacity to make decisions and give informed consent.

We should assume support will be needed unless there are grounds to show otherwise. What the support involves will depend on the client. It could range from whānau, communicative assistance, use of an Easy Read translation or linking a person to an advocate eg Health and disability advocate, Disability organisation, VOYCE for a young person in care or legal guardian.

Conclusion

We can’t avoid or shy away from the reality that we are often working with clients in coercive contexts. But there are still many opportunities for a client to exercise choice about engaging with your service.

Yes, engagement is about manaakitanga and skilled work. It’s also about respecting and supporting a person to make their own decisions and give or not give consent in an informed way.

Your Informed Consent policy is important not just to comply with accreditation standards but because it supports client empowerment and authentic and transformative relationships with clients.

Q and A Family violence information sharing

Changes to support information sharing about family violence are due to commence on 1 July 2019. Here’s some Q&As about what’s coming.

Q-Why is information-sharing being changed?

answer

Death reviews have shown missed opportunities to respond to family violence. The new information-sharing provisions aim to address this.

Q-Who’s affected?

answer

The new law applies to family violence agencies and social services practitioners. Both are defined broadly. Community services receiving government funding to help victims and/or to stop perpetrators of family violence, licensed early childhood services, schools and specified government agencies are included.

Q-What’s the change?

answer

There are some legal requirements. The gist of the changes is that if you’ve got information that could help another agency working with a person impacted by family violence then consider sharing it. It’s not compulsory to share the information but it is compulsory to consider sharing it.

This is important particularly for people working in health-related agencies who often feel conflicted about their duty of confidentiality versus sharing information.

Q–What happens if I share info?

answer

As long as you share information in good faith and are careful you wont be liable. You should check the relevance of the personal information requested or that you’re thinking about disclosing (eg is it relevant to a client’s assessment or plan?)

Q–What if a client doesn’t want to share their info?

answer

The point of the change is that safety rather than consent should drive information sharing.

Best efforts should be made to obtain a person’s consent to sharing their personal information and you should consider their views. But even if consent is withheld, you might decide the information should be shared eg to help with safety planning.

Q–What about a client’s trust?

answer

This is often a big worry. People trust us with information and we want to honour that trust. But the new law means we don’t have to put this above protecting a victim from violence.

We can still build and maintain trust. But it needs to be done from the start. Clients should be informed when welcomed to the service that personal information may be shared if it will help protect a victim of family violence. Transparency should then be maintained throughout the relationship when and if their personal information is shared for family violence reasons.

Q–What does it mean for policies?

answer

We’ve been updating our online policy service for members. Policies that are being updated include those dealing with privacy and planning.

We’ve had a lot of people join us lately, but it’s still a good time to join.

It takes about 8 weeks to get you online. But we’ll put you online with your policies updated. From then on, we regularly review them and keep them up-to-date.

Contact us if you need a hand.